Compared to China, India has far greater wealth disparity

Date : Feb 2, 2015

US President Barack Obama chose his State of the Union Address to demand a better spread of wealth through a brand of "middle-class economics". He joins many leaders from the developed world in calling for action on inequality. Where is India headed and where should it be headed?

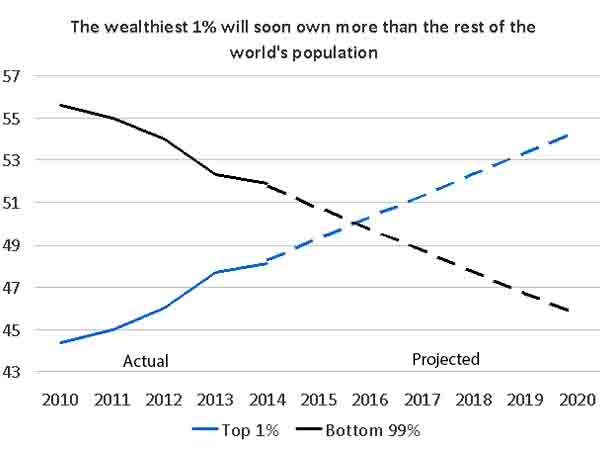

‘Wealth: Having it all and wanting more’ , a research paper published by Oxfam in January 2015, shows that the richest 1 percent have seen their share of global wealth increase from 44 percent in 2009 to 48 percent in 2014, and at this rate, it will be more than 50 percent in 2016. The 80 richest people on the planet have the same wealth as the poorest 3.5 billion people, the report says.

Data source: Oxfam

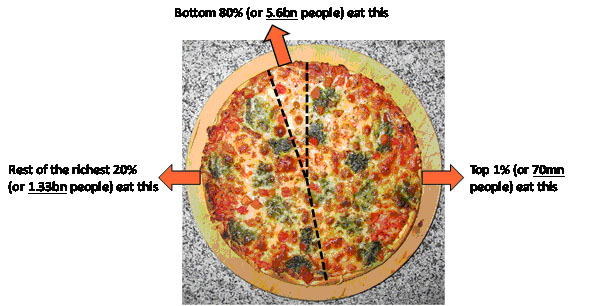

Of the remaining 52 percent of global wealth, almost all (46 percent) is owned by the rest of the richest fifth. The remaining 80 percent share just 5.5 percent. Stark enough–even more simply, think of global wealth as a pizza.

Little wonder then that obesity is likely to overtake hunger as the top global health issue.

While the post 1990s economic boom led to large increases in wealth, thus pulling many out of abject poverty, disparities have grown because public policy is dictated by the rich–lobbying, access to finance and tax havens help enrich the rich.

Data source: CSFB Global Wealth Databook 2014

The Indian context

A new report on inequality in South Asia released by the World Bank shows that concentration of billionaire wealth in India (12 percent of GDP) is unusually large for economies in the same stage of development. This is borne out by trends in wealth distribution:

The two charts above say a lot about India’s wealth building journey:

• The 2008 crisis saw concentration peak and proved to be a leveller of sorts

• Share of the very wealthy is higher in India, but China’s catch-up is by far the steepest

• At the start of the economic boom, India’s wealth concentration lagged that of North America, but by 2014, India’s rich owned a larger portion of wealth than North Americans do

• The starkest statistic: While the trend in top decile wealth is broadly in line with other countries (and well below the global average), the top percentile’s share of wealth is at 50 percent, ahead of any other part of the world

When compared with China, India has far greater wealth disparity as shown by the comparison of Gini Coefficients (higher Gini coefficients signify greater inequality in wealth distribution, with 1 being complete inequality and 0 being complete equality). While India’s income-based Gini (which measures disparity in per capita GDP) shows much greater equality than in China, the wealth-based Gini shows much greater disparity.

Data source: World Institute for Development Economics Research

The gap between the ‘have-a-lot’, the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ is clearly much larger in India. India’s rich are disproportionately richer while India’s poor are disproportionately poorer than their global peers. In layman’s terms, there is an even larger share of pizza going around for the richest of the Indian rich. And it’s growing.

For Indians, excess wealth (which sounds like an oxymoron to most) has ended up in under-utilised real estate in Dubai, London and New York (real estate advisory firm Knight Frank suggests that on average, wealthy Indians park 44 percent of their investments in real estate), private jets that have no space to be parked and operate under onerous restrictions besides luxury yachts docked all over the globe due to poor (!) infrastructure at home… next up, private islands. While one shouldn’t grudge those who have earned their keep in an honest manner, the utility of wealth needs to be defined and understood better.

The question for India really is that can a country ranked 135/187 in the UNDP’s Human Development Index afford persistent and growing wealth disparity? The HDI reflects long-term progress in three basic dimensions of human lives--a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. Despite being a much larger economy and growing at a faster rate than its regional peers, India’s progress on HDI has been dismal due to poor social indicators.

Why this matters?

This isn’t just about morality-inequality plainly hurts economic growth (or will some day); a better balance actually sets the foundation for sustainable growth. Equitable distribution would be beneficial for many reasons:

• The aspirational poor tend to take on too much leverage in order to achieve a lifestyle of a certain order, thus creating boom-bust cycles at the micro and macro levels

• The less rich spend a much larger portion of their wealth. The uber-rich can buy only so many homes or cars. Hence, growth will accelerate only when wealth is more evenly distributed

• Costs of inequality are borne by the rich, eventually:

-

First order cost effects of inequality are in the form of schemes such as NREGA, FSB, fuel subsidies, etc, borne by the entire tax-payer base

-

Second order effects come from a stunted future for the world where malnourished and under-educated sections of the population deflate notions of a demographic dividend

-

Third order effects are social disorder, rise in terrorism, Naxalism, street crime, disease, etc. The rich cannot wish these problems away nor can they insure themselves against these, beyond a point

-

Take the case of ebola or closer home, dengue for instance, long considered a poor man’s disease, prevalent in a world very distant from the rich. Focus and funds have built up only when they began to cross national and social boundaries

Wealth: A Means to an End

Two of the three richest men in the world, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett (worth over $150 bn combined), have committed most of their wealth to charity. Additionally, Bill Gates is funding and promoting market-based, sustainable, for-profit initiatives across the world to end poverty, improve education and boost sanitation while Buffett has convinced 128 billionaires to join his ‘Giving Pledge’ . Back home, Azim Premji has already committed 25 percent of his $18 billion wealth to charity.

So the answer to the question, ‘What would you do (for yourself) with a billion dollars?’ is, in the case of some billionaires, ‘Not much’.

Alongside this increasing disparity, commercialisation and a consumerist social order, terms like ‘minimalist living’, ‘freelancing’, ‘volunteer work’ and ‘sabbaticals’ are also entering the Indian business dictionary. An increasing number of people are looking for that deeper purpose or true calling.

The common thread: Obtaining wealth is a means to something, not an end in itself.

Even as trends suggest a staggering disparity in wealth distribution, in a globalised world, the interests of the rich and poor will increasingly converge. An investment in equality would thus be an investment in one’s own future.

![]()